Can an angry, allegorical one-hour play – written in the 80s at the dawn of the Western AIDS crisis, set in a dystopian New York and featuring a street-talking heterosexual couple fiercely navigating the new dangers of intimacy – can it still tickle and provoke? Does it resonate with today? Does its emotional machinery still have an impact? The answer isn’t simple.

We first meet Torch as the lights go up, naked and sweating, performing pull-ups in a hellish downtown hovel. He’s soon joined by Blue, who has risked her life to join him. Torch is in quarantine, yet to show the signs of the infection that is eating up the planet. Blue, still clear of the virus, is desperate to touch her lover, to kiss him, to fuck, even if these intimacies could lead to her death. It’s a story of passion and possibly love, a fight for a kind of freedom in the face of terrible odds and bodily functions. The action that follows is simple: a couple argue over whether to have sex. The stakes, however, are far from domestic. In this world, sex can easily equal death.

Writer Alan Bowne died of complications related to AIDS in 1989. He wrote Beirut just as the HIV epidemic was on the rise in the Western world. So it’s clear why the virus of his play bears so much resemblance to HIV. To the audience of 1984, the parallels would have been obvious and challenging, pulled from the real world around them, stoking their personal fears. But what about the audience of 2018, more than 30 years later?

We’ve seen a lot since 1984, a lot of plays that deal directly with the impacts of HIV: The Normal Heart, My Night With Reg, Angels In America. We’ve seen musicals: Rent, Falsettoland, The Last Session. And we’ve seen plenty of plays from writers that test our limits: Sarah Kane, Mark Ravenhill, Ella Hickson, Martin McDonough, Anne Washburn, Anthony Neilson, Phillip Ridley, Caryl Churchill, Branden Jacob-Jenkins. What’s more, we live in a medicated age of treatments and knowledge. Our lives are also dangerously digital: where the atrocities of power are all-too apparent and persuasion is pervasive. We are toughened and experienced, and maybe cocooned … maybe a little cynical about the obvious, the poetical, the blunt and sincere. All of the things that Beirut lays at our feet.

But it’s for this very reason – audience experience – that Beirut not only keeps its power, it grows while you watch, and keeps growing once you’ve gone, tapping your mind as you make your way home.

Martin Sherman’s Passing By was also written at a time of moral panic and sexual punishment. Sherman’s story was similarly simple: the negotiations of two lovers as they fought the restrictions of illness. Only here the illness was not HIV, despite expectations. Sherman neatly side-lined HIV to focus on the interplay of people: the illness here was hepatitis.

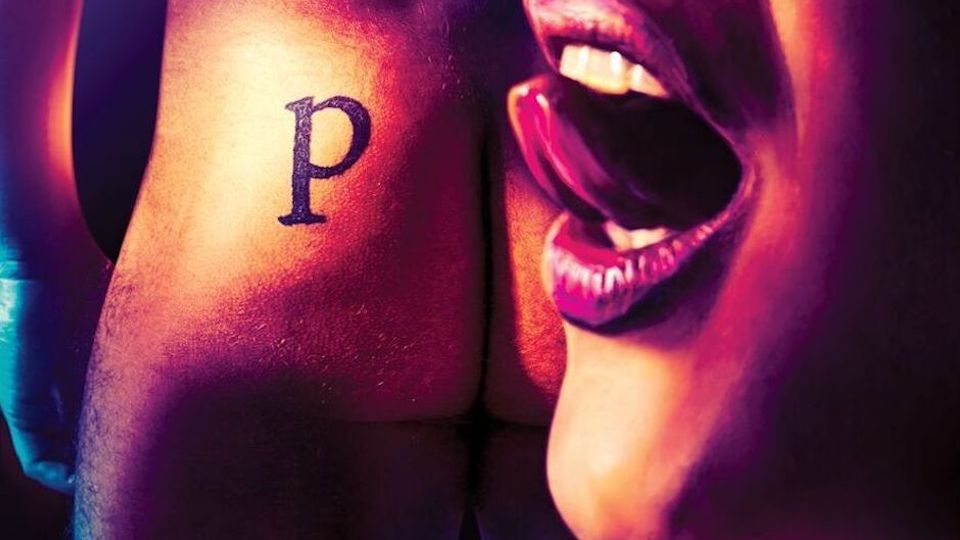

Similarly, Bowne side-steps the obvious: his couple are straight, not gay. They are East-Side stock, from the district of Queens, rough and sharp and sexual, confident in their opinions. Their names are poetic: Blue and Torch. Evoking the lighting of blue-touch paper and fireworks, maybe even erotica and lip-synch. The dramatic design, just as with Sherman, is to use the virus as a back drop, and not the thing itself. In the words of Sontag, a famous New Yorker: “illness is metaphor”.

In this light, Beirut is not about disease or physical dysfunction. It’s a way of talking about life, the broader canvas. The idea is there when Blue talks about risk: “I can live without sex and feel dead or risk death and feel alive”. Even the disease is lyrically brought to life, when Torch talks about a disease “that puts coffee stains on your underpants and snot in your water glass”. We’re not anchored in the literal: our minds are encouraged to wander.

Like the salty, poetical language, the characters are also designed to connect beyond specifics. The performances are nuanced, not representing. Louisa Connolly-Burham (Blue) and Robert Rees (Torch) work hard to bring this sweaty New York future to life. They ooze sex and an earthy East Side swagger, their accents growing in confidence as the hour ticks by. Director Robin Lefevre has them grind and tease, but also open up and transform as they each push their agendas. Together, the team create a typically domestic battle that morphs into an argument for love.

The promo material for Beirut draws parallels with recent epidemics and health scares: SARS, Zika and BSE. But I think this misses the point. This is not a play about disease. Nor does this production play it as one. It is a story about how we handle the sudden changes to our physical and political world. To be felt as something that connects with everyday fears and realities.

If I had one reservation, it would be the more overt sexualization of Blue, the way she’s made to bow down and be weaker on two occasions. For the woman that recognises the hell of her world with humour, this feels a little dated: stripping and succumbing when it suits to titillate. But it’s a minor point when ultimately she gets her way and powerfully proves her point.

Is Beirut a play for our times? Can it do as it did in its day? No. This is not the same provocation it was back then. It’s possibly more. More of what Bowne intended. More abstract and therefore more powerful. It blends the actual world and the imagined, and talks to us about what keeps us sane, keeps us together in this increasingly controlling world. It’s a tricky and artful piece that’s given plenty of humanity in this revival. And it’s a play that lives on in the head, long after its short, sharp almost-shock.

Cast: Louisa Connolly-Burnham, Robert Rees Director: Robin Lefevre Writer: Alan Bowne Theatre: Park Theatre Duration: 60 mins Performance dates: 12 June – 07 July