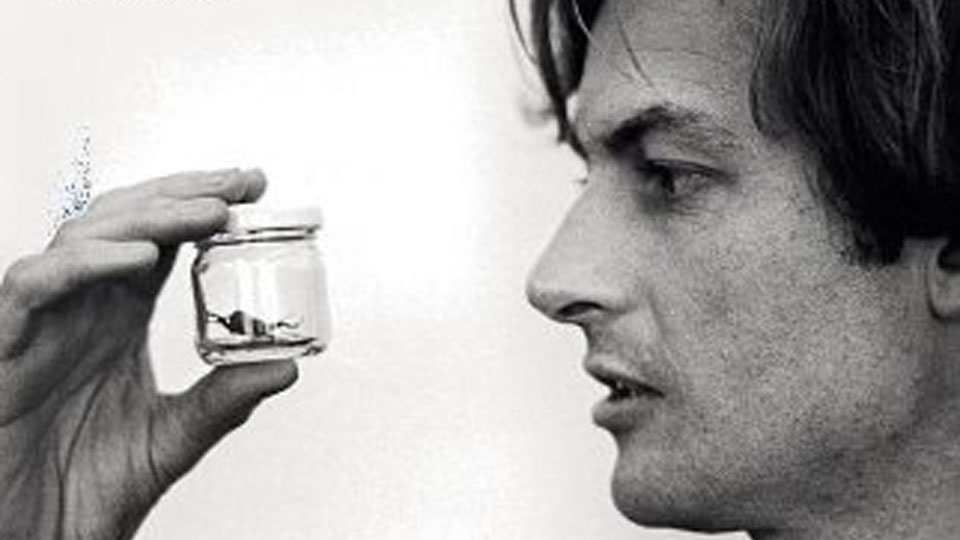

An eminently readable memoir, Richard Dawkins’ An Appetite For Wonder recounts the scientist and author’s early years and traces the development of his intellectual ideas. There are quite a few surprises, not least that Elvis Presley indirectly persuaded young fan Dawkins into a short-lived religious fervour! You’ll also find out what a dundridge is, and why Dawkins dislikes them.

There’s a good reason why Richard Dawkins has achieved the rare distinction of becoming a member of both the Royal Society and the Royal Society of Literature. His rational mind and great intelligence has seen him produce major contributions to his specialist field of zoology and specifically evolutionary biology. His brilliance with words, clarity of thought and passion for explaining his subject has seen him pen over a dozen popular science books in the last four decades, since the publication of The Selfish Gene in 1976 which became an instant bestseller. Richard Dawkins is one of those writers whose voice you can hear resoundingly clearly in your head as you read his prose: the attainment of such a unique and immediately identifiable style one of the greatest achievements for any writer.

An Appetite for Wonder is Dawkins’ first attempt to write about another subject that has long-fascinated his readers: himself. It is a memoir of his formative years, a chronological account starting with the circumstances of his birth in Nairobi and ending with the publication of The Selfish Gene when he was in his mid-30s. The second half of his life will be recounted in a further volume due to appear in a few years’ time.

Whilst biographical works have been attempted by others, An Appetite for Wonder is the first time Dawkins has revealed much about his personal history beyond his scientific work and intellectual ideas. It is a useful addition to his canon: after all, it’s about time we were given the real story of what makes Richard Dawkins Richard Dawkins, especially since anyone with strong feelings one way or the other about (of all things) religion has a multitude of preconceived ideas based on his television documentaries and panel show appearances. What comes across is a mild-mannered man of boundless intellectual curiosity; unrecognisable from the shrill, strident caricature beloved of lazy Fleet Street hacks.

The narration of Dawkins’ childhood is it a poignant evocation of a British colonial way of life now gone, but it’s also remarkable for his honesty in relaying that the exotic flora and fauna of Nyasaland were not the things that fired his enthusiasm for the natural world and the biological sciences. Indeed, Dawkins paints himself as an unremarkable child, something shared with other great thinkers like Albert Einstein, and he repeatedly returns to the theme of the cruelty of children, though not necessarily in relation to himself.

He paints the background of the Dawkins clan with great affection for his ancestors and with the economy of a seasoned writer. Genealogy interests most people, but of course Dawkins can weave in his passion for genetics as he introduces us to his forebears, one of whom, General Sir Henry Clinton Dawkins, was partially responsible for British loss of the Americas during the reign of George III.

Dawkins’ schooldays are equally evocative, and his account of having to adapt to life in cold and rainy England is poignantly captured, since it was clearly a painful time. His insight into the English public school system is interesting, and Lindsay Anderson’s remarkable satire on it, ‘if…’, had already sprung to mind before the author cited it. Much ink has already been spilled concerning Dawkins’ descriptions of the mild forms of sexual abuse he suffered, but his attitude towards it is objective and honest. He doesn’t shy away from such self-analysis, justifying his contempt for self-delusion. There’s even an awkward passage, faintly embarrassing even to read, in which he recounts the loss of his virginity (to a cellist…)

Whilst the relaying of intimate personal moments are likely to capture the lion’s share of headlines and speculation, An Appetite For Wonder is mostly a scientist’s memoir, akin to Medawar’s Memoirs of a Thinking Radish, and Dawkins’ readers will relish later chapters when he goes into some detail about his early research work at Berkeley and Oxford. Noted for his endearingly Herodotean digressions, Dawkins also relates his years of computer programming, even though, in the author’s view, the obsession took up time that could have more usefully been deployed elsewhere.

It is in capturing his close friendships and collaborations the author brings warmth and wit to the memoirs. The early chapters strongly feature his parents and uncles, but the later chapters introduce us to influences like Niko Tinbergen, Bill Hamilton and others of his noted scientific peers. Allowing his readers to glimpse the real Dawkins, the book is flushed with a multitude of quotations from beloved poetry which, as Dawkins admits, render him embarrassingly prone to shed a tear.

Perhaps out of respect for others, he subjects only himself to analysis, revealing little about his personal life with others, or indeed, his marriages. This is appropriate: An Appetite for Wonder is a memoir about ideas and a way of thinking, and a privileged access into the mind of one of Britain’s greatest living scientists. That’s the book the author set out to achieve, and he does so with characteristic charm, pith and humanity.