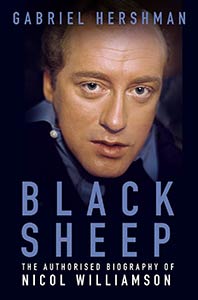

Noted biographer of under-rated actors, Gabriel Hershman, returns with a thorough and compelling narrative on the life and career of Nicol Williamson. Who? Certainly too many people would ask that, especially now, several years after his death in 2011, and effectively two decades after the end of his career. Nicol Williamson, however, is a name still revered by lovers of British theatre, who may remember, or have had passed down in legend, whispers of his era-defining 1969 Hamlet, or his star turn in John Osborne’s Inadmissible Evidence, all of which is celebrated in this volume. Unforgettable to those who were captivated by him, yet largely forgotten by wider audiences (except those who grew up marvelling at John Boorman’s Excalibur, in which Williamson played Merlin, his best-known screen outing); this is the story of what might have been, and a legend who never quite was…

Noted biographer of under-rated actors, Gabriel Hershman, returns with a thorough and compelling narrative on the life and career of Nicol Williamson. Who? Certainly too many people would ask that, especially now, several years after his death in 2011, and effectively two decades after the end of his career. Nicol Williamson, however, is a name still revered by lovers of British theatre, who may remember, or have had passed down in legend, whispers of his era-defining 1969 Hamlet, or his star turn in John Osborne’s Inadmissible Evidence, all of which is celebrated in this volume. Unforgettable to those who were captivated by him, yet largely forgotten by wider audiences (except those who grew up marvelling at John Boorman’s Excalibur, in which Williamson played Merlin, his best-known screen outing); this is the story of what might have been, and a legend who never quite was…

Black Sheep is a tale about an actor, what stage craft means, and the effect of a larger-than-life personality within a profession that demands cooperation with others in order to stage a production. It’s an interesting observation to make that Hershman returns to a subject matter than dominated his first biography (via an analysis of Albert Finney‘s impact on the world stage), his excellent account of the life if Ian Hendry: that of self-destructive behaviour, about which he appears to be a dedicated student. This area is certainly of interest to the author, as is the psychosis that drives great and talented people to – effectively – ruin their own chances. Black Sheep contains multiple stories that reveal, as with Hendry, Williamson’s drinking was out of control. Yet he seems not to have been a complete alcoholic, like Hendry, whose life was cut short through his demons. Williamson’s self-destruction has different roots, and Hershman carefully teases them out during the course of the book.

Without wishing to prejudice readers, or provide too many spoilers, it’s perhaps worth summarising in brief that Williamson’s self-destruction was essentially a refusal to play the game and to cooperate with other people. Was it so much a bad boy reputation he developed that held him back? Hellraisers like Ollie Reed, Richard Harris, Peter O’Toole, Richard Burton, John Hurt, Anthony Hopkins (the list in British theatre and film is a long one…) could secure work and see their Rabelaisian behaviour accommodated; with Williamson, we see a repeated pattern of unreliability and prickliness that seems to be driven by a quest for artistic integrity and perfection. Here’s the great frustration of the book: nobody’s life or career, however talented they are, is without compromise or a history of having to work their way upwards from lowly origins. The author tries not to be judgemental about this – inferring personal convictions and principles as motivating factors – but as the chapters progress, it becomes (at times, frustratingly) clear that Williamson’s under-appreciation stems from his erratic and poor behaviour that others find hard to excuse or put up with. Why should they? The moral of the story is clear: talent alone is never enough. Play the game and pay your dues, or you’ll end your career in god-awful rubbish like Spawn…

Black Sheep is thoroughly researched and draws on multiple first-hand accounts to build a clear portrait of Williamson both as a human being and an actor. The actress Jill Townsend, who was married to Williamson for a period, offers some very moving reflections on a turbulent romance and relationship, which the space of decades and the death of Williamson couches in loving and understanding terms. The primary source is Luke Williamson, their son, who also provides a brief foreword.

Luke clearly adored, and was adored in turn by his father, and in supplying the insights for this book, had a fruitful collaboration with the author, who provides lengthy quotations to allow Williamson’s nearest and dearest to tell the story in their own words. There are other contributors from writers, actors, directors and producers who worked with him – some of them long-suffering, others who enjoyed the experience of hiring him. They also offer some of the amusing anecdotes that are scattered throughout the book, even though the long drinking sessions with Carolyn Seymour, for example, pointed to her own demons. There is a hilarious account by Luke, which also serves to illustrate Williamson’s purist spirit, where Mick Jagger attempts to introduce himself to Nicol during dinner at the Ivy. Let’s just say the subject of the book wasn’t star-struck.

Hershman does a great job of presenting the facts of Williamson’s life and career, making few judgements and allowing the reader to draw their own conclusions. There is often an element of damage-limitation – establishing the truth about certain outrageous behaviours such as jumping in the Thames to impress Lindsay Anderson, or various punch-ups over the years with unlucky colleagues, which may (or may not) have been exaggerated and embellished. The author also defends Williamson’s corner, agreeing with the late actor’s assessment that his talent as a performer and singer outshone that of Richard Harris (despite, or perhaps because of their obvious similarities, the two were not friends), without following through the conclusion that Harris recorded multiple albums, and with MacArthur Park, enjoyed an unlikely smash hit in the charts (the best song ever recorded?) What’s painfully obvious by the end of the book is Williamson’s lack of drive or ability to rely on others to actually get something off the ground, and despite his love of music, the nearest he came to recording anything was with a local group in Rhodes. The author, excellent in the part of defence, is often reluctant to join such dots.

That’s not to say that Black Sheep doesn’t present a fully-rounded picture of Nicol Williamson – it does. A complex character who was perhaps even something of a lone wolf, the life and spirit of Williamson comes to life in these pages, and will be preserved by them too. Black Sheep is a labour of love, and the author touchingly adds his own brief encounter with his subject. Such touches, as well as including some of Williamson’s school boy poetry and the stories of those who knew him best, serve to make Black Sheep an excellent, personalised biography that is unashamedly reverential of the subject matter. If you love actors and Twentieth Century theatre, or enjoy accounts of great men crushed under the weight of their personality flaws, you’ll enjoy getting lost in the pages of Black Sheep.

Publisher: The History Press Publication Date: Feb 2018