Peter Craze is a familiar face from British theatre and TV, with roles in cult favourites such as Doctor Who and Blake’s 7. He’s also a director, and his latest show, The Trials of Oscar Wilde, is currently embarked on a major UK tour.

We caught up with Peter between performances to chat about the play. Over a lively conversation we learned about how he worked with Oscar Wilde’s grandson on the script; the little-known background to Wilde’s downfall and imprisonment; and how the play reflects current social issues, especially concerning gay rights.

Along the way Peter gave us his memories of his time in television of the 60s and 70s, explaining why Tom Baker was so much fun; what Peter Howitt’s like to collaborate with, as well as why he’s so fond of working in America.

Peter, you’re directing The Trials of Oscar Wilde. Tell us about the show.

It’s open now and it’s touring. It’s striking quite a chord. We’ve had some very nice reviews, and it’s been an exciting journey because it was slightly difficult to see how we could do it. Merlin Holland, who is Oscar Wilde’s grandson, is the co-author with John O’Connor, and they wanted it to be verbatim rather than a dramatization that might have an attitude, standpoint or agenda. They used all the transcripts of the libel trial, which is still extant and on record, and they culled together the two criminal trials that happened afterwards and used documentation, letters, journal reports and newspaper clippings. It was a tricky one because I was away in America, and we were to-ing and fro-ing and I could see as a director that it was going to work very well, but it needed theatricalising slightly.

How did you get involved?

Well the whole reason the show came about, which is the same for everybody, is we all know about Oscar Wilde and something about him going to prison, but we don’t often actually know the details about what happened. When I started researching I became fascinated because it was such a quagmire of Victorian homophobia. It was absolute persecution, and the more I dug around about that the more fascinated I became, but Merlin is sixty-seven, and this is his last tribute to his grandfather (though of course he never met him), and he just wanted the facts to speak for themselves. We did a lot of research and development with the actors, and in the end we’ve come up with what I think is a very good format. Virtually every word is from De Profundis, the transcripts or newspaper articles. What was interesting for me is the horror that lay behind it, the fact that Bosie, Lord Douglas, was Oscar Wilde’s lover: but his older brother Francis was alleged to have been Lord Rosebery, the Prime Minister’s lover. They wanted to keep the whole thing subdued so of course they went for Wilde almost as a smokescreen. All this stuff is fascinating but they wouldn’t let me go into it in too much detail, though we managed to get some of it in, but the focus is on the man of letters and the morality of his existence as an artist against his sexual proclivities.

Was there a compromise you and Merlin reached?

There wasn’t a lot of compromising (laughs). There were things that he just would not entertain being in the actual play. Funnily enough I had a run-in with one of the Samuel Beckett estate in New York when I directed a staged reading of Beckett’s first play. I got to meet his nephew. Later I came back to London and I to see if I could get this production on. His nephew said to me: “Peter, I have to tell you, my whole life has been taken up by my fucking uncle!” (laughs) I think the same sort of thing is true for Merlin, though he has become a champion of Oscar. Beckett’s nephew didn’t want to deny him, but your life is taken over…

It’s a double-edged sword perhaps.

Yes, but then again Merlin’s written some wonderful biographies and compilations of letters that have also given him an income, but the preservation and honesty of Wilde’s reputation has always been something Merlin has been particularly keen to shield and look after. So it’s been a fascinating journey and in fact we’re still tinkering with it. There’s a possibility, after we’ve played at the St James Theatre in London at the end of this tour, of taking the show to America and playing it off Broadway. There’s an American producer looking into it, so it might be reworked yet again. The joy of this tour is that we’re getting a lot of feedback. You never really finish a play, frankly.

You’ve done a lot of work in America.

Yes I have, so I have a lot of very good contacts over there. This particular play would be incredible off Broadway. It wouldn’t be massive, but it could become very much a rallying call for a lot of issues that are very current in New York and beyond.

Some of the themes are still very topical.

Very much so. What was fascinating putting the play together and being involved in it was this whole cult of celebrity sexual prosecutions that are going on now, from Jimmy Savile on the one hand to William Roache on the other, and you have Rolf Harris on trial at the moment. The difference in Victorian times was the whole morality of the era, which was homophobic to the point of hysteria.

It’s certainly a timely show, with equal marriage in the UK, and an increasing number of states in the US.

I was directing Noël Coward’s Blithe Spirit in Iowa in the autumn, in Cedar Rapids, and discovered that it was one of the first states to approve of gay marriage. I was very surprised: it’s a sort of corn field, hog farm kind of state! But they’re very tolerant and all the rest of it.

Tell us about the actor playing Wilde.

It’s John Gorick and he’s really quite stunning in it. He has a real passion for it; but one has to stop him becoming a flag bearer for Wilde and anything he saw as the persecution of Wilde.

Had you worked with the actors before?

I knew one of them because I was principal of a drama school and he was a graduate from there, and the other two I knew of but I hadn’t worked with them, so it was very exciting to have that opportunity. They’re all extremely good. As well as John, there’s Rupert Mason and William Kempsell in the cast. I think they think it’s their property, frankly! (laughs) It’s been very much a collaborative effort. John O’Connor and Merlin Holland are the writers, without a doubt. But what works and what doesn’t work very much comes through exploration in rehearsals. We were still rewriting it on the Wednesday before we opened on the Saturday, which was brave of the actors to allow, but it was necessary and the show has benefited from it. We’ve had lots of positive Tweets and letters, which is very encouraging.

What is it about Oscar Wilde that continues to fascinate us?

I think it’s almost Shakespearean: he brought about his own downfall without a doubt. He was stupid to take the libel case against Lord Queensberry, Bosie’s dad. He didn’t need to do that. It was almost in a fit of pique, because he absolutely and supremely thought they’d just dismiss it and he’d get off. In fact two weeks before the case came to court, he went to Monte Carlo with Bosie, so sure was he of acquittal. If he’d stayed in London he might have realised what was mounting up for him. So you’re watching the downfall of an ordinary man, who is also a genius, an extraordinary playwright and a brilliantly witty man. But at the same time he fraternised with the rent boys and the low life of London. But you could almost say it’s the equivalent of pornography on the internet today. There is a vulnerability in all of us, and Wilde said, “I’m an artist, I’m allowed to love beauty, and I see beauty in young boys, what’s wrong with that?” Let’s not forget that Oscar Wilde was such a flamboyantly defiant figure. He makes us all think: “Well, maybe we should get up and shout a bit more.”

Yes, that’s a lovely juxtaposition. We think of the late Victorian era as repressive, yet here was this, like you say, very flamboyant character.

Yes, which was fine until he over-stepped the mark. What I discovered in the research is that what was behind it all is that Wilde transgressed the ultimate sin: he went with working class boys.

We simply couldn’t have that, could we?

That’s right. It was all right for Rosebery, the Prime Minister, to go with Francis, Lord Douglas’ brother, because that was all part of the aristocracy and it was kept within the family, so to speak. Wilde went out of his way to go to local brothels and work with young impish rakes and blackmailers, and that world fascinated him. He went too far. In prosecuting one of his own class, Lord Queensberry – that was sacrilegious, so they really went for him. There was a deal done with the solicitor general to prosecute him criminally. The trial finished at three o’clock and he was arrested by six thirty. Within the aristocratic family, they allowed him two hours to leave the country if he chose to.

But of course he didn’t.

He said, “I’m an Irishman, not an Englishman, and I stay.” (laughs) He had the witticisms and the epigrams even in moments of terror, because it must have been horrifying for him when he realised he was really going to go to prison for two years. He came out a broken man. He never really wrote again properly, and died within three years.

That was the expectation with hard labour. And he must have died thinking his plays would never be performed again.

They were taken off. The Importance of Being Earnest had just opened when the libel started. On the first night Queensberry delivered his bunch of rotten vegetables to the stage door, and said, “Make sure Mr Wilde gets these.” Within 86 performances the play was closed. He had stepped outside the morality and the etiquette of the period. But there’s a lot about Wilde’s imprisonment and death that most people don’t know a lot about. The play, without being a history lesson, has encapsulated that time of his life very well.

So audiences can learn a lot about the downfall and death of Oscar Wilde?

Yes, and they can see it. It’s almost like a nail-biting last episode. You can see him walking right into it. He’s asked questions like, “Did you kiss the boy?” and he responds, “Oh, no. He was far too ugly.” To which the QC replies, “Excuse me, did you say ‘ugly’?” It’s the beginning of him admitting that he did kiss pretty boys, but not ugly ones. There was new criminalisation against homosexuality in the UK that came out in 1885, which stiffened the penalties, and of course Oscar Wilde caught it. I’m not sure they weren’t looking for someone to make an example of, quite frankly, to show that the new law was effective.

It still goes on in many countries.

Yes, and until not very long ago in this country. Some of my good chums were banged away for it. I’ve been in the theatre a long time, and some of our top actors and top directors were prosecuted. It was only in 1967, after the Wolfenden Report that homosexuality was decriminalised in the UK. It’s been fascinating learning all this and becoming an expert for a few weeks!

You mentioned earlier that you’re looking into taking the show to the US. Do American audiences still go in for Wilde?

Oh, absolutely. I’ve directed a lot of shows in America and the most I’ve done besides Shakespeare is Oscar Wilde and Noël Coward.

Do you have a fondness for America?

I love it. I lived in San Francisco with my family in the eighties. Running the Drama Studio, which I was principal of until two years ago, they had a branch over there. I got to know lots of nice and creative people and they liked what I did, and they kept inviting me back. I have a great love for the place, although the thinking and the whole ethos of the country has changed in more recent years. It’s not quite as confident as it used to be. I see that reflected in the youngsters I work with in universities and drama programmes.

What do you put that down to?

I think it’s the changing global position, and America no longer thinks of itself as supreme. I think Obama’s a brilliant president, and it might be a good thing for Americans to lose some of that arrogance. 911 had a big effect, and I don’t think it’s yet been really detailed to just what extent it impacted the American people. But certainly the youngsters are far less confident and much more insecure – just like the English! (laughs)

Welcome to our world!

We always had a lot of American students at the Drama Studio because of the American connection, and they were wonderful. They’d come in with their noise and their arrogance and they’d lift up the English spirits! Now it’s all gone a bit grey. Maybe that’s a reflection of the social times we’re living in.

Do you have a preference for acting or directing now – or even teaching?

I’ve sort of done with teaching. I feel I’ve explored it as much as I can and there’s a younger set of teachers who are coming up. Like I say, I was principal of Drama Studio London, and I believe the training of young students is important. I’ve remained on as an associate, and I work with the students as a freelance director and will be doing so with a play I’m starting in a couple of weeks which will be staged at the Tristan Bates Theatre: but I think it’s important that they’re working with much younger people who are currently at the coal face. I love doing their graduation productions because they’re trained, they’re not wimpish babies just out of university.

The Tristan Bates Theatre is a lovely space too, isn’t it?

It’s super. The play I’ll be directing there is about baby farming in the 1950s. It’s called Women of Twilight by Sylvia Rayman, which was done in 1952. It’s a precursor to Look Back in Anger, in a way, which came along four years later. It was the first working class play, and it was written by a woman, which is fascinating. But out of directing and acting, I much prefer directing: simply because I’m used to being in control and in command of the whole operation! (laughs) When I go back to acting, which isn’t very often these days, but if I do some filming I just become a silly actor: I have no director’s hat on at all.

Is it nice in a way, to not have to be in control for a change?

Absolutely! It’s like going on holiday. You’re basically saying, “Well, you do it, mate.” (laughs) But I’m lucky enough in that all my time is taken up with directing at the moment. I haven’t the time to go chasing acting parts, unless somebody phones up and asks me to do an episode of EastEnders or something, which I like to do because it keeps me connected to acting – but as a director as well, which is important.

As we’ve touched on acting, I’ll ask you about some of the productions you’ve been in. What are your thoughts about Johnny Speight’s If There Weren’t Any Blacks You’d Have to Invent Them?

Oh my goodness, that’s going back a bit!

1968!

Yes, that’s right. That was an extraordinary piece, and Johnny was around then, of course, but drinking very heavily. He was supposed to turn up and do rewrites, but we never saw them. You couldn’t do it today, it was so outrageous. It was a bit like Till Death Us Do Part [Speight’s later sitcom] in that it was looking at prejudice, but it really went a bit far. It was redone with Richard Beckinsale some years later. But I was asked about the fiftieth anniversary of Doctor Who because I did one in 1963 with Bill Hartnell, and the question was about what it meant to me: but it was just another job, frankly. Only history creates its legend and its importance, but at the time it was just a good and a well-paid job. John Castle was in it, a terrific young actor, as he was then. It was just wonderful working in television in that era, because many of the dramas were fairly prominent.

You mentioned Doctor Who just then. You were in three serials with three different Doctors [The Space Museum with William Hartnell, The War Games with Patrick Troughton and Nightmare on Eden with Tom Baker]. Do you have any explanation as to why the show is so enduringly popular?

They always moved the programme with the times and with the technology. The appeal will always be there. Having said that, I showed my granddaughters some of the ones that I’d done, and they walked out of the room saying it was really boring. Whereas Matt Smith they can sit and watch for hours! It’s no reflection on myself (laughs), but they’ve moved the programme to today, which is brilliant and very clever.

Your most prominent role was probably the one with Tom Baker, when you were a sort of intergalactic policeman.

That was great. I loved doing that, because Tom was as mad as a hatter. Brilliant to work with: so exciting and dangerous. I remember when he threw the director [Alan Bromly] out. He said, “Get out of here, go and play with your silly camera script. You don’t know about Doctor Who and you don’t care about Doctor Who. I am Doctor Who!” All these wonderful things were goings on!

To have been a fly on the wall! You were a lovely double act with Geoffrey Hinsliff in that one.

Yes, you’re right! Geoffrey. He was very funny, very good. We deliberately worked out a kind of Laurel and Hardy quality. I still go to the conventions occasionally. I don’t do too many, but they’re a lot of fun. It’s remarkable: fifteen year olds will come up to you. You wonder what on earth they’re doing watching the old ones, but they tell you all about them.

How wonderful.

And it makes them happy, so why not?

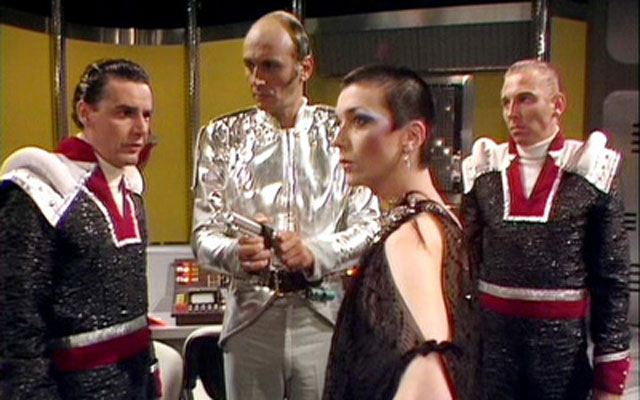

Quite right! And another cult favourite you were involved with was Blake’s 7. You did two of those.

Yes I did. I liked that. They were talking about bringing it back, weren’t they?

There have been rumours. I interviewed Sally Knyvette not that long ago for EF and she told me they’re still just rumours…

It wouldn’t be us lot anyway. It would be like an old pensioners’ club! (laughs) But they were great fun and they were great times for television. There was about ten or fifteen years when there was a great bunch of directors and bloody good actors, and they turned it in and had fun, and they all knew each other. For a couple of years I knew exactly what I was doing for the year ahead with television series. It was a very happy and very secure environment. Vere Lorrimer directed one that I was in [Seek-Locate-Destroy] and he was a lovely old boy. He would always say, “Come on chaps, stop mucking about and let’s have a practice.” (laughs) It was a golden era for drama really. Theatre moved through a period where it was getting a bit static, but all this wonderful television came along, and it was the new form of drama in a sense. I think it’s still great now, I don’t want to harp on about the good old days, and all that nonsense!

Slightly more up to date, you were in the British movie Dangerous Parking, directed by Peter Howitt, who was also in it.

Yes, that was wonderful. I was very cross that it didn’t do well. Not for me, I was only in one scene. It’s a very funny scene and we expanded it: but I was cross because I thought it was a bloody good film. But because Peter directed it, wrote or adapted it, produced it and so on… He didn’t want to star in it, but the lead actor they had lined up pulled out at the last minute. So what he got was people saying Peter Howitt’s big-headed. They built him up after Sliding Doors, and all those lovely films he did, and then it was time to knock him. I still think it’s a good film. I think it captures a wonderful period in drugs and rock and roll.

I would agree. I saw it at the time and favourably reviewed it.

Peter’s a lovely lunatic. I liked him a lot. He’s in Canada now, directing and starring in a television series [Reasonable Doubt]. They don’t mind that sort of thing over there: in fact they think it’s great. It’s why I work in America a lot, because they allow people to do what they want to do without pigeonholing them too much.

Thank you very much for talking to us about your career and the show, Peter. We wish you every success with the tour of The Trials of Oscar Wilde, and we’ll look out for Women of Twilight in the near future.

Great stuff. Lovely to talk to you.

The Trials of Oscar Wilde, directed by Peter Craze, is currently touring the UK. You can find out if it’s stopping in a theatre near you and book tickets by checking our news article about the show.