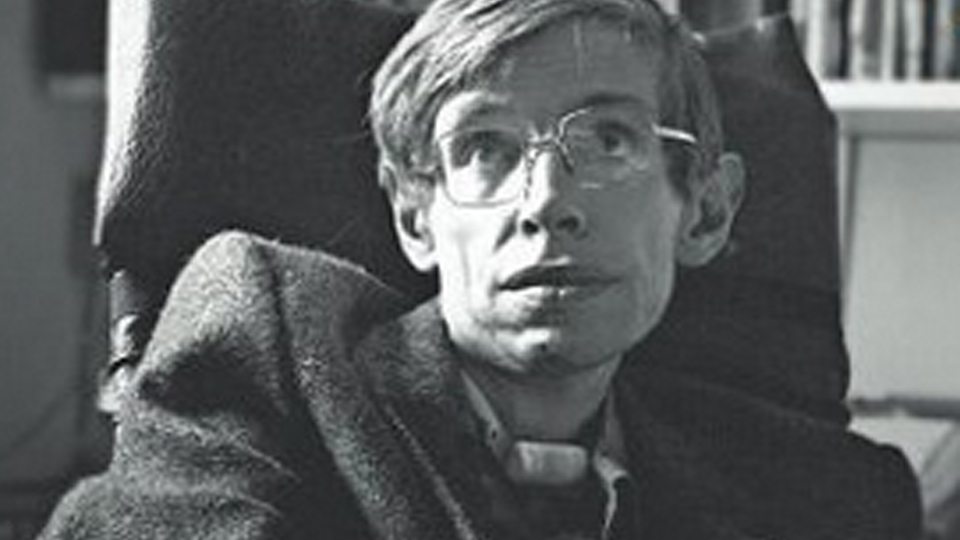

Stephen Hawking is one of the greatest scientists and popularisers of science of our time. In a new biography,Stephen Hawking – His Life and Work, his personal acquaintance Kitty Ferguson gives a thorough account of Hawking the man, as well as of his extraordinary body of work in cosmology, especially in the areas of black holes and the origins of the universe that has changed and challenged our fundamental understanding of reality.

What lies at the heart of Hawking’s research throughout his life is a straightforward if ambitious goal: “A complete understanding of the universe, why it is as it is, and why it exists at all.”

Ferguson opens her account with a flair for the original which makes much of the tome highly readable. Rather than start at the moment of Hawking’s birth, she begins with a potted history of the issue that has preoccupied Hawking for much of his professional life – the search for the Theory of Everything – the scientific understanding that will unite the very large with the very small – cosmology with quantum mechanics.

The narrative of Hawking’s childhood is beautifully recounted, and Ferguson conveys a delightful sense of the close, if eccentric family life that he enjoyed whilst growing up in a dark, draughty and ill-cared for old house amongst doting parents and siblings. His father’s concern that there’s no future apart from teaching in mathematics seems, in retrospect, absurd and endearing: yet the prodigiously talented Hawking, who like so many great minds was a mediocre performer at school, earns his way to a scholarship at Oxford University. Hawking’s famous wit and self-assurance is nicely highlighted in an anecdote about how he persuaded the board at Oxford to allow him to transfer to their great rivals Cambridge to pursue his doctorate.

The human element most obvious in the retelling of the life of Stephen Hawking is of course the early onset of his debilitating illness, Motor Neurone Disease, symptoms of which first appear when he is a student in his early twenties. With the prospect of an early death (doctors at first gave him only a few more years to live – he will turn seventy early next year) Hawking faced the choice of languishing in self-pity or concentrating his brilliant mind to work in the time available to him. His academic career speaks for itself, and Ferguson is keen to emphasise the point that Hawking refuses to let his disability prevent him from living a full and active life that has involved trips all over the world, including Antarctica; meetings with heads of state; several bestselling books; children and grandchildren; numerous academic awards and even an experience of a zero-gravity flight.

Ferguson’s challenge is to condense as much of an extraordinary seven decades of life so far as she can into 350 pages. The human elements of Hawking’s childhood, marriage, fatherhood and illness are beautifully told, and there’s the very real feeling not just that Ferguson knows Hawking well and has done for a long time, but that she genuinely cares for him and his family.

Lay scientists may be more daunted by the account of Hawking’s work, and herein lies the most challenging task for Ferguson – how on earth to make the mind of a genius whose work in cosmology is so highly specialised readily understood to a mere few accessible to a wide readership? For the most part, she succeeds in much the same way that Stephen Hawking himself succeeded with A Brief History of Time: there are excellently clear descriptions of the large issues and precious few off-putting mathematics and equations. It wasn’t until the tenth chapter that I, who left maths and physics behind long ago, lost the thread of the argument and acknowledged that there are some things I simply won’t grasp no matter how patiently and simply they are relayed. As soon as the narrative moved on I picked up the thread again. Hawking’s extraordinary work can be a challenge to understand and convey to readers of popular science, but it is rewarding to persevere, and learning about what motivates Hawking to work is what marks this book out as a worthwhile accompaniment to Hawking’s own canon of writing.

It helps to have a strong interest in science in appreciating this book; but then a biography about one of the foremost scientific geniuses of our age is unlikely to attract too many casual readers, and Ferguson pitches the balance between Hawking’s personal life and an explanation of his work about right.

One less successful aspect of Ferguson’s narrative is the constant patronising reassurance she gives the religionists that Hawking’s work doesn’t disprove their deity of choice. It seems especially at odds with Hawking’s latest tome, The Grand Design (the biography follows a linear chronological path, and the book, and the furore it provoked in the popular press, is discussed in the final chapter), which hit the headlines for its claim that Hawking’s understanding of the origins of the universe requires no divine creator. Ferguson’s constant reassurance on this point seemed incongruous, as the pious are unlikely to take an interest in a biography of Hawking, and it may have been better to duck the issue altogether.

The overriding sense is that Kitty Ferguson has, through self-evident admiration for Hawking and his work, endeavoured to understand the great scientist as a human being, and has directed her warm but by no means gushing biography at similarly interested lay readers who also harbour an interest in the fundamental questions that have gone some way to being answered by Stephen Hawking, who has laid the groundwork and set challenges for future generations to unravel.